Two recent events have indicated escalating trade tensions in the clean-tech sector.

On May 14, the United States said it would significantly increase, from Aug 1, tariffs on a range of Chinese exports, mainly clean-tech products such as new energy vehicles (100 percent), solar panels (50 percent) and lithium batteries (25 percent).

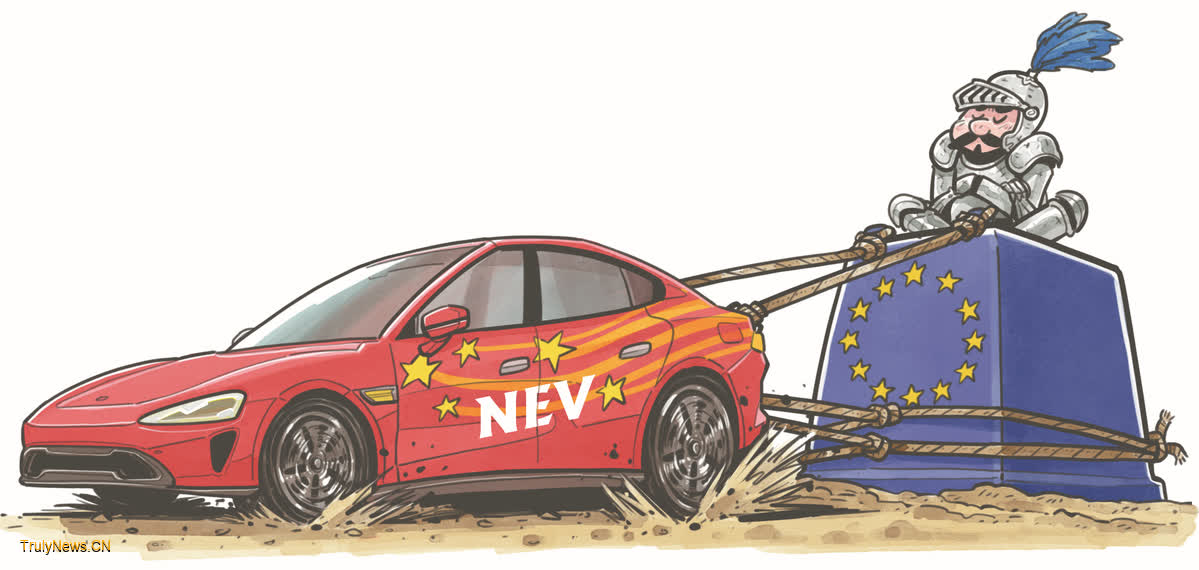

On June 13, the European Commission announced the preliminary results of its ongoing investigation into so-called Chinese NEV subsidies, concluding that China’s NEV value chain benefits from “unfair subsidization” that hurts EU rivals, and planning tentatively to impose extra tariffs ranging from 17.4 percent to 38.1 percent on NEV exports from China.

Indeed, the underlying rationale for the (countervailing) tariffs on China as advocated by the EU is highly similar to that of the “overcapacity” (or, more accurately, the “predatory overcapacity”) allegation of the United States, both claiming that China’s competitiveness in clean-tech products in general, and NEVs in particular, derives from the subsidies they receive, thus constituting predatory pricing, resulting in flooding of exports to the detriment of relevant industries in importing countries.

The argument, however, is highly misleading, if not unfounded.

Even US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen admits that “overcapacity” is “a complicated issue that involves China’s entire macroeconomic and industrial strategy”. Admittedly, there may be some sign of overcapacity in some clean-tech sectors, but this is far from “predatory overcapacity” backed by industrial subsidies, as the US asserts, and the competitiveness of Chinese clean-tech industries is not bolstered by industrial subsidies, but by the dynamics of China’s factor endowments at this stage.

To industry insiders, those signs of overcapacity are more likely to be the product of a boom-bust cycle driven mainly by spontaneous market process, as relevant industries are entering a mature phase in their respective technology/product life cycles.

For example, in the case of NEVs, for the past 20 years, Chinese companies have been making early strides in this field in a systematic manner, making substantial R&D investments successively, and gradually building up their unique technological edges.

Moreover, China has a huge market; its sustained investment in STEM research and higher education has ensured a steady stream of the so-called “engineers’ dividends”; rich application scenarios, full-fledged competition (even to the extent of so-called “involution”), and frequent interactions between the supply and demand sides and among relevant participants have all enabled an ongoing optimization of the value chain ecosystem.

Through years of competition and cooperation (including cooperation with foreign companies), a highly cost-competitive, efficient and comprehensive NEV supply chain has gradually taken shape in China. In short, in the NEV industry, China is increasingly demonstrating a clear comparative advantage, consistent with the dynamics of its factor endowments at this stage.

In fact, over the last decade, thanks to the technological, manufacturing and engineering progress of Chinese companies, the global average costs of wind/solar power generation and lithium batteries have fallen significantly, making a significant contribution to the global transition to green and low-carbon energy.

Against the backdrop of the global energy transition and after years of development, the NEV, lithium battery and PV industries have so far entered the mature phase of the technology/product life cycle. In this phase, a dominant (technological) design emerges, and the market becomes commoditized. Accordingly, the competition increasingly revolves around price, and there is usually a shakeout, characterized by large-scale capital investment (in the dominant technology/design) to grow volume and bring down costs, leading to fierce price wars and the exit/consolidation of competitors.

Overall, an industry in this phase often exhibits signs of overcapacity, which is the natural result of industrial development driven mainly by spontaneous market forces.

The consequence of protectionist measures that unfairly target China will only result in the shift of production from a low-cost (more efficient) country to a higher-cost (less efficient) one.

As Singaporean scholar Lance Gore sharply pointed out, Yellen’s argument “is practically saying that the US cannot compete with China’s ‘new trio’ but the US workers’ livelihoods must be protected, so production capacity must be allocated, and the benefits shared”.

Meanwhile, these recent events have shown that the Sino-American trade disputes have further spread to clean-tech sectors closely related to climate change. However, China-US cooperation on climate change has long been viewed as a special bond that helps to stabilize the relationship between the two countries during difficult times.

Moreover, another major global geopolitical player, the EU, has also become involved in trade tensions with China, which adds to the geopolitical complexity that China faces.

If trade disputes over clean-tech products continue to escalate, the foundation of trust for China-US climate change cooperation (and also for that between China and Europe) will be undermined, impeding any further substantive climate cooperation between them and making it much more difficult to achieve global climate change goals.

On a more practical level, disruptions in the supply chain of clean-tech products will slow down the deployment of renewable energy projects worldwide, affecting efforts to combat global climate change.

In the process of readjusting/restructuring the global new energy industries, it is necessary for all major global players to effectively communicate and cooperate with each other to jointly address global challenges and put the world economy back on track.

As Stephen Roach put it bluntly, “to take a protectionist stand against a country like China — that has a comparative advantage in producing the non-carbon, alternative energy products that a world in the grips of climate change desperately needs — is a blunder, potentially of historic proportions”.The author concurs.

The writer is president of the University of International Business and Economics.

The views don’t necessarily reflect those of China Daily.